Spinach has long been celebrated as a nutritional powerhouse, with generations of parents encouraging their children to eat their greens because “spinach makes you strong.” This reputation stems largely from spinach’s perceived iron content, a mineral essential for healthy blood and overall vitality. Popeye the Sailor Man popularized the idea that consuming spinach provides extraordinary strength, cementing in popular culture the notion that this leafy green is among the best sources of iron available. However, the scientific reality of the amount of iron in spinach is considerably more nuanced than cartoons and conventional wisdom suggest. Understanding the actual iron measurements in spinach, how your body absorbs that iron, and what factors influence bioavailability can help you make informed dietary decisions and optimize your iron intake from this nutritious vegetable.

This comprehensive guide examines the precise iron measurements in spinach, explores why the iron in this leafy green is surprisingly difficult for your body to absorb, and provides practical strategies for maximizing the nutritional benefits of spinach consumption. Whether you’re concerned about iron deficiency, following a plant-based diet, or simply curious about the science behind food nutrition, this article will equip you with the knowledge to understand what spinach actually contributes to your iron requirements.

Raw Spinach Iron Content: Numbers vs. Reality

The actual amount of iron in spinach ranges between 2.1mg and 2.7mg per 100g of raw vegetable, with the USDA specifically recording approximately 2.6mg of iron per 100g. This measurement represents the total iron content present in the vegetable tissue, but as subsequent sections will explain, this figure does not directly translate to the amount of iron your body actually absorbs and utilizes.

Why Raw Iron Content Misleads Consumers

When comparing raw iron measurements, spinach technically contains slightly more iron than beef sirloin steak, which has approximately 2.5mg per 100g. This surprising comparison explains part of spinach’s iron reputation. However, this raw comparison requires critical qualification, as the form of iron and its bioavailability differ dramatically between plant and animal sources. Spinach also exceeds kale’s iron content (approximately 1.7mg per 100g), though both leafy greens share similar challenges with iron absorption.

Understanding Iron Classification Standards

To properly contextualize spinach’s iron content, understanding regulatory labeling standards provides valuable perspective. For a food to be marketed as a “source of” iron, a 100g portion must contain at least 15% of the recommended daily intake (approximately 2.1mg of iron per 100g). Spinach meets this threshold. However, to qualify as “high in” iron requires double that amount (approximately 4.2mg per 100g). By this standard, spinach falls significantly short of the higher classification. This regulatory positioning demonstrates that while spinach contributes meaningful iron to your diet, it doesn’t qualify as an exceptionally iron-dense food compared to other options.

Spinach Iron vs. Other Iron-Rich Foods: An Honest Comparison

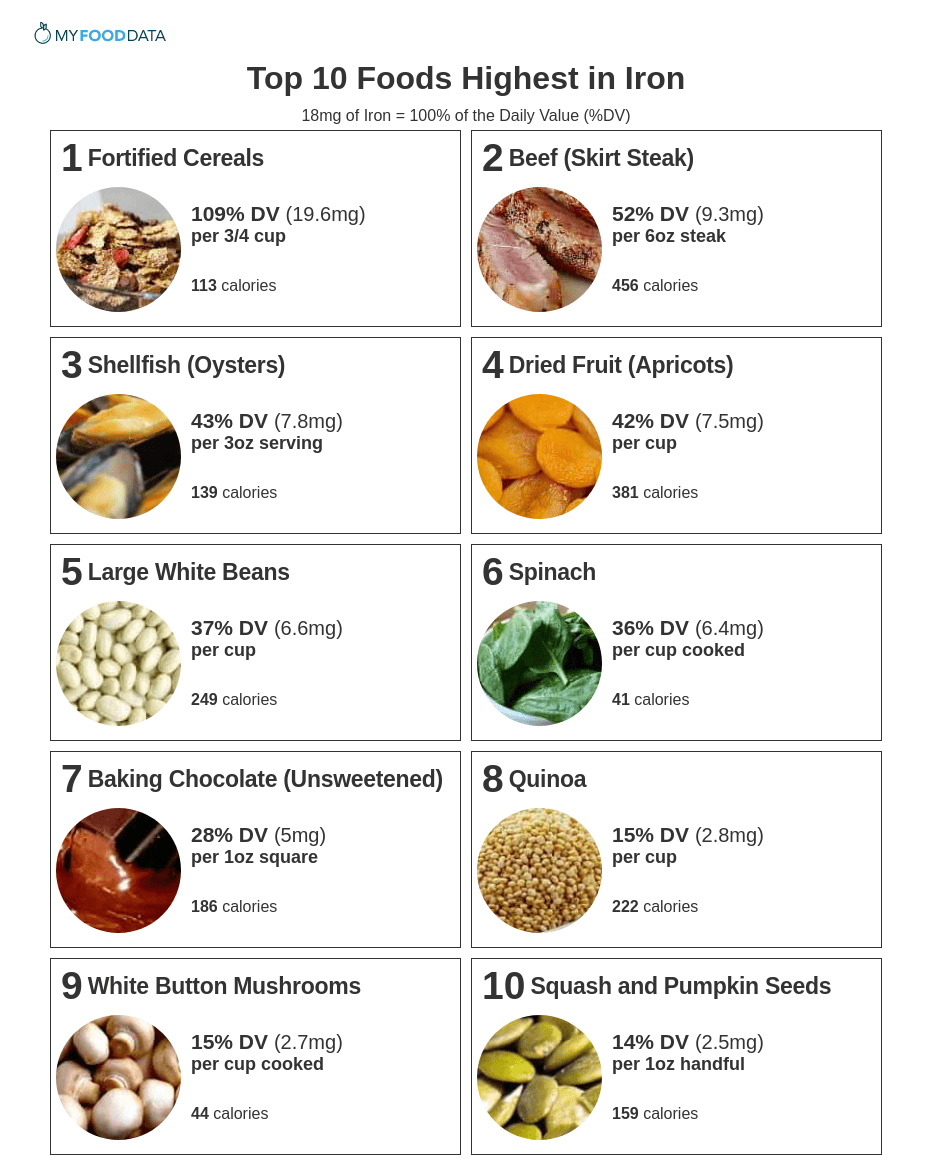

When examining the amount of iron in spinach alongside other iron-rich foods, the vegetable’s iron content appears relatively modest despite its reputation. Fortified cereals contain a staggering 67.7mg of iron per 100g, dried apricots provide approximately 6.3mg per 100g, while beef delivers approximately 5.5mg per 100g. Both spinach and kale contain approximately 1.7mg to 2.7mg of iron per 100g, positioning them similarly among plant-based sources, though spinach consistently measures slightly higher than kale.

The practical implications of these figures become clear when considering meal planning. To obtain equivalent total iron intake from spinach compared to other sources, you’d need to consume substantially more spinach by weight. For example, you’d need to eat nearly 2.5 times more raw spinach than beef to get the same amount of iron on paper—but the real story involves bioavailability, which makes the difference even more pronounced.

Why Only 2% of Spinach Iron Gets Absorbed

The iron content in spinach presents a significant bioavailability challenge that dramatically affects its nutritional value and practical contribution to your dietary iron needs. Scientific studies have demonstrated that as little as 2% of the iron from spinach is actually absorbed by the body, with some measurements indicating approximately 1.7% absorption of the non-heme iron content.

The Bioavailability Math You Need to Know

Consider the practical implications: when you consume 100g of raw spinach containing 2.6mg of iron, only approximately 0.044mg of iron is actually absorbed and utilized by your body. In comparison, 100g of beef sirloin steak containing 2.5mg of iron, with an approximately 20% absorption rate, results in roughly 0.50mg of usable iron. This represents an absorption difference of more than tenfold between the two food sources on a per-gram basis.

Why Heme Iron Absorbs Better Than Spinach Iron

The fundamental difference in absorption stems from the form of iron present. Iron in meat appears predominantly as heme iron, which is highly absorbable and resilient to gastric pH changes. Heme iron’s molecular structure allows efficient absorption through specific intestinal transport mechanisms.

In vegetables like spinach, iron exists exclusively as non-heme iron, which is inherently more difficult for the body to absorb. Non-heme iron absorption is readily influenced by various dietary factors and compounds that either enhance or inhibit its uptake, making plant-based iron far more variable and generally less bioavailable than animal-derived heme iron.

Cooking Spinach to Improve Iron Absorption

Despite the challenges with the amount of iron in spinach, specific cooking methods can significantly enhance your body’s ability to absorb what iron is present.

Boiling Methods That Reduce Oxalates

Boiling proves to be highly effective at reducing oxalate levels in spinach. Research shows that boiling spinach for 12-15 minutes reduces total soluble oxalic acid concentration from 975mg to 477mg per 100g, representing a reduction of approximately 51%. The key insight: always discard the cooking water rather than using it in preparations, as this ensures leached oxalates are removed from your final meal.

For practical home cooking:

– Use a large pot of rapidly boiling water

– Add spinach and cook for 12-15 minutes

– Drain completely and press out excess water

– Discard cooking water immediately

This simple technique can improve iron absorption from spinach by nearly doubling the bioavailable iron content.

Strategic Food Pairings That Boost Iron Uptake

Beyond cooking methods, strategic dietary combinations dramatically improve non-heme iron absorption:

- Vitamin C pairings: Add citrus fruits, bell peppers, tomatoes, or strawberries to spinach dishes to increase iron absorption by two to three times

- Heme iron combinations: Pair spinach with meat, poultry, or fish to leverage the “meat factor” that enhances non-heme iron absorption

- Avoid inhibitors: Don’t consume tea, coffee, or calcium-rich foods within one hour of eating spinach

Pro Tip: Create a spinach salad with sliced strawberries, orange segments, and grilled chicken for maximum iron absorption potential.

Daily Iron Requirements vs. Spinach’s Contribution

Understanding your daily iron requirements provides essential context for evaluating spinach’s role in meeting your nutritional needs.

Adult men over 19 require 8.7mg of iron daily, while women aged 19-50 need 14.8mg due to menstrual losses. Given spinach’s 2% absorption rate, meeting women’s iron needs through spinach alone would require consuming several kilograms daily—clearly impractical and potentially causing digestive distress.

Practical Reality Check: One cup (30g) of cooked spinach provides approximately 0.8mg of iron, but only about 0.016mg gets absorbed. To meet a woman’s daily requirement through spinach alone would require eating approximately 925 cups (27.75kg) of cooked spinach daily!

Beyond Iron: Spinach’s True Nutritional Value

Despite limitations as an iron source, spinach offers substantial nutritional benefits that justify its inclusion in a healthy diet:

- Rich in carotenoids: Particularly beta-carotene (vitamin A precursor) that supports vision and immune health

- Excellent vitamin K source: Essential for blood clotting and bone health

- High folate content: Especially when cooked, supporting cell function and tissue growth

- Low calorie density: Provides substantial nutrients with minimal calories

- Magnesium and potassium: Important for muscle function and blood pressure regulation

The green chlorophyll in spinach masks the orange coloration that beta-carotene imparts in other vegetables, but the nutritional benefit remains substantial regardless of appearance.

Maximizing Iron Absorption: Your Action Plan

To get the most iron from spinach while enjoying its other nutritional benefits, implement these evidence-based strategies:

- Always cook spinach: Boil for 12-15 minutes and discard cooking water to reduce oxalates by up to 50%

- Pair with vitamin C: Add lemon juice, bell peppers, or tomatoes to every spinach dish

- Combine with meat: Include small portions of meat with spinach meals to boost absorption

- Time your beverages: Avoid tea, coffee, and calcium supplements one hour before and after spinach meals

- Rotate iron sources: Don’t rely solely on spinach—incorporate lentils, beans, and fortified cereals

Critical Warning: If you’re managing iron deficiency, don’t rely on spinach as your primary iron source. Consult a healthcare provider about appropriate supplementation alongside dietary changes.

Spinach’s Iron Reality: Key Takeaways

The actual amount of iron in spinach (2.1-2.7mg per 100g raw) meets the threshold for being a “source of” iron but falls short of “high in iron” classification. However, the form of iron in spinach and absorption inhibitors mean only about 2% gets absorbed—making it a relatively poor source of utilizable iron compared to many other foods.

While oxalic acid (approximately 1000mg per 100g) has historically been blamed for poor absorption, current research suggests polyphenolic compounds may play a larger role. Regardless of the mechanism, spinach should be viewed as one component of a varied diet rather than a primary iron source.

Spinach’s value extends well beyond its iron content. Its rich carotenoid profile, low calorie density, and diverse vitamin and mineral composition make it a valuable addition to any healthy eating pattern. By understanding both the limitations and strengths of spinach as a nutritional source, you can make informed decisions about how to incorporate this versatile green into your overall dietary strategy for optimal health.