Nothing ruins a cooking experience faster than discovering your beloved cast iron skillet has developed serious seasoning problems. That once-smooth, naturally nonstick surface suddenly flakes onto your food, feels sticky to the touch, or shows patches of rust despite regular use. Cast iron seasoning problems strike fear into even experienced cooks because they threaten to transform a trusted kitchen companion into a frustrating liability. Understanding why these issues occur and how to fix them properly means the difference between a pan that performs beautifully for generations and one that ends up in the back of your cabinet.

Most cast iron seasoning problems stem from preventable mistakes in preparation, oil selection, temperature control, or maintenance routine. Whether you inherited a vintage skillet with questionable seasoning or your newer pan developed issues after your last oil application, this guide addresses the root causes behind common seasoning failures. The good news is that with proper diagnosis and technique, nearly every seasoning problem has a straightforward solution that restores your pan to peak performance.

Why Your Cast Iron Loses Its Seasoning

Seasoning breakdown happens gradually or suddenly, and understanding the underlying mechanisms helps you prevent future problems. The polymer bonds that create that protective coating are surprisingly resilient when properly formed, but several factors can weaken or destroy them.

Heat damage from excessive temperatures ranks among the most common causes of seasoning failure. When cast iron exceeds roughly 500-600°F for extended periods, the polymerized oil begins to break down, causing the surface to become brittle, discolored, and prone to flaking. This often happens when people preheat their pans empty on high heat for too long or place them under broiler elements. The seasoning essentially “burns off” in patches, leaving bare iron exposed.

Acid exposure poses another significant threat to your seasoning. Tomatoes, wine, citrus, and other acidic foods can strip away newly-formed seasoning if left sitting in the pan too long. The acid reacts with the iron and breaks down the polymer bonds, particularly on fresh seasoning that hasn’t fully cured. This is why many cast iron experts recommend cooking acidic foods in enameled cast iron rather than plain carbon steel or traditional cast iron.

Improper cleaning practices destroy more seasoning than almost any other cause. Scrubbing with harsh detergents, soaking the pan in water, using steel wool, or letting the pan air-dry without proper maintenance all compromise the seasoning layer. Water exposure on bare iron leads to rust, which destroys seasoning from underneath, while abrasive cleaning removes seasoning from the top.

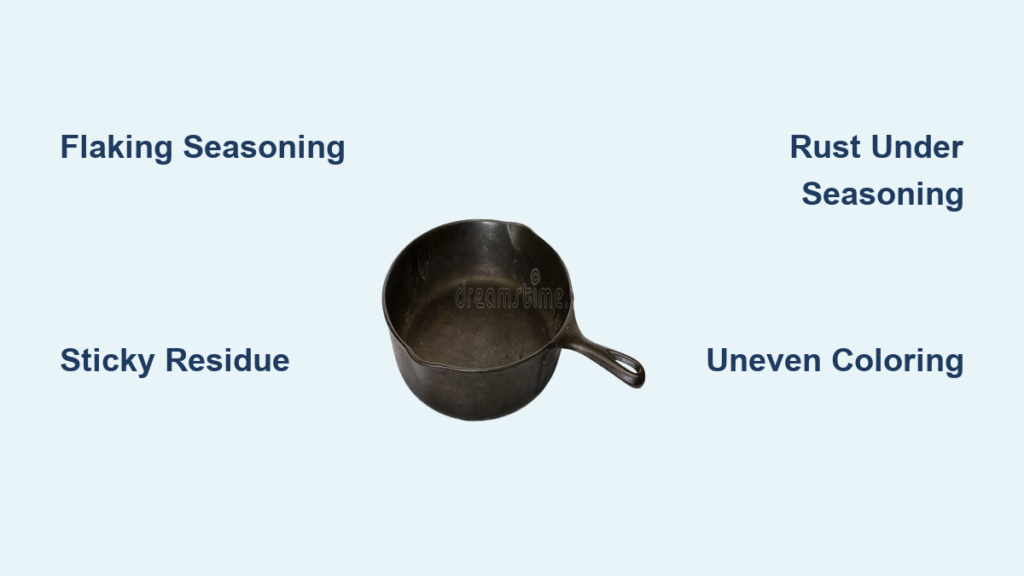

Diagnose Flaking and Peeling Seasoning

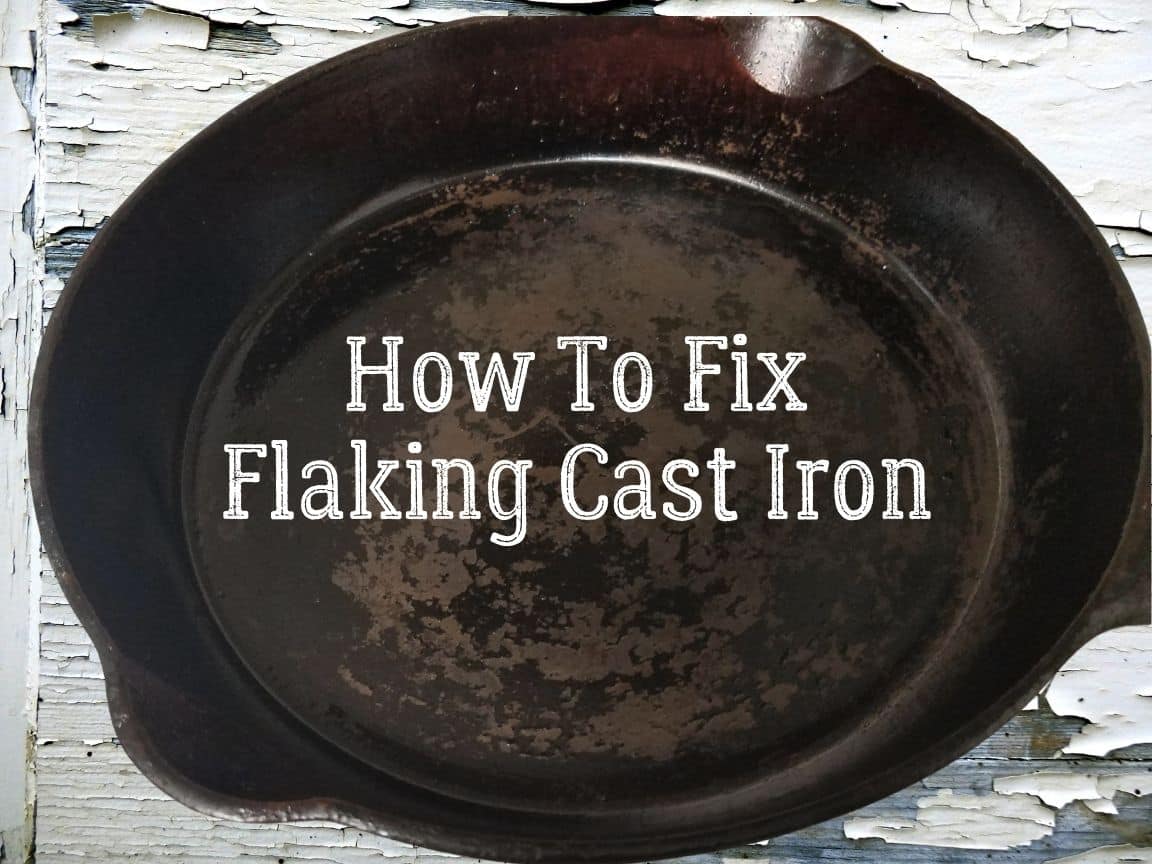

Flaking is perhaps the most frustrating cast iron seasoning problem because it seems to happen suddenly and spreads throughout your pan. One day you have a smooth nonstick surface; the next, you’re pulling tiny black flakes off your food. This issue almost always traces back to problems in your seasoning process.

Inadequate surface preparation before seasoning creates a foundation that can’t hold the new oil layer. Any rust, old seasoning residue, or debris left on the iron prevents fresh oil from bonding properly. The new layer adheres weakly and eventually lifts away in sheets. Always thoroughly clean and dry new or stripped cast iron, then apply oil to a slightly warm pan to ensure proper absorption.

Using the wrong oil creates seasoning that looks fine initially but fails under cooking conditions. Oils with low smoke points—olive oil, vegetable oil, and many “seasoning blends”—burn before polymerizing properly or create soft, unstable layers. The ideal seasoning oils include flaxseed oil (highest polymerizing potential), grapeseed oil, avocado oil, or rendered bacon fat, all with smoke points above 400°F and favorable fatty acid profiles.

Rushing the seasoning process by applying thick oil layers or skipping proper curing time produces soft, gummy seasoning that peels away. The key principle is “thin and even”—apply oil, then buff away virtually all of it until the pan appears dry. Build up layers gradually over multiple sessions, allowing each to fully cool before the next application. Thick layers never fully cure through to the iron, remaining sticky underneath while the surface seems fine.

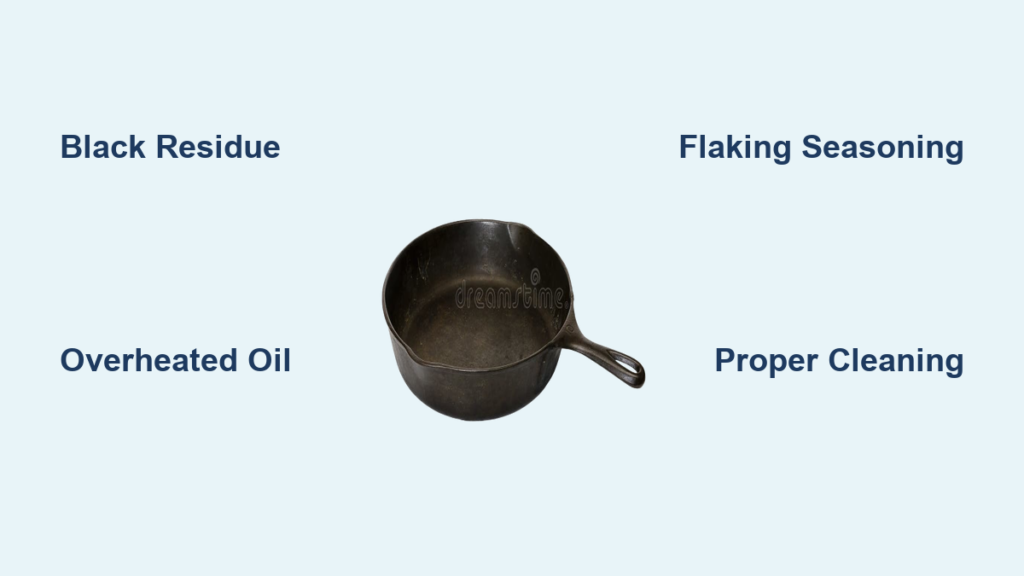

Fix Sticky and Gummy Seasoning Residue

Sticky seasoning feels wrong the moment you touch it, and it ruins food by pulling ingredients apart during cooking. This problem occurs when oil fails to fully polymerize and remains in a semi-liquid state. The surface feels tacky, picks up dust and debris, and transfers onto everything it touches.

Over-oiling during application is the primary culprit behind sticky seasoning. When you apply too much oil, the excess can’t evaporate or polymerize properly. It remains as a sticky film that never fully cures. The solution involves stripping the pan completely and re-seasoning with a dramatically reduced oil amount. Dip a paper towel in oil, then wipe it almost completely dry on a clean cloth before applying to the pan. The pan should look dry when you’re finished—no visible shine or wet appearance.

Insufficient heat during curing prevents proper polymerization. If your oven temperature runs low or you didn’t preheat fully, the oil never reaches the chemical reaction temperature needed to bond. Always season at 400-450°F and verify your oven’s actual temperature with an oven thermometer if possible. Some home ovens run 25-50°F below their setting, which can mean the difference between successful seasoning and sticky failure.

Humidity interference affects the curing process more than most people realize. In humid climates or during rainy seasons, excess moisture in the air can prevent proper oil polymerization. If you consistently get sticky results, try seasoning in a different environment—perhaps a garage with climate control, or use a food dehydrator set to low heat as an alternative curing chamber.

Address Uneven Coloring and Patchy Seasoning

Ideal seasoning develops a deep, uniform brown to black color across the entire cooking surface. When your pan shows inconsistent coloring—light spots, dark patches, or concentric rings—it indicates uneven oil application or varying heat distribution during curing.

Inconsistent oil distribution leaves some areas with too much oil and others with too little. The over-oiled spots darken more and can become sticky, while under-oiled areas remain light and may not develop proper nonstick properties. Solution: always apply oil in thin, uniform layers using a fresh section of paper towel for each pass. Work the oil around systematically, covering every inch before buffing away excess.

Hot spots in your oven create uneven curing because some areas of the pan receive more direct heat than others. Electric ovens often have hotter spots near heating elements, and gas ovens concentrate heat at the bottom. Rotate the pan halfway through each curing cycle, and consider using a convection setting if available to promote more even heat distribution.

Old or degraded oil on your pan before application interferes with new layer bonding. If you’re adding fresh oil to existing seasoning without cleaning properly, old oil residues mix with new application and cure unevenly. Always start each seasoning session with a clean, dry surface.

Treat Rust Underneath Intact Seasoning

Finding rust developing beneath what appears to be healthy seasoning is alarming but fixable. This scenario typically occurs when moisture penetrated the seasoning layer through micro-cracks or weak spots, beginning corrosion that lifts the seasoning from below.

Moisture intrusion points usually stem from thermal shock—pouring cold water into a hot pan, taking a hot pan outside in cold weather, or placing a hot pan on a cold wet surface. The rapid temperature change causes the iron and seasoning to expand and contract at different rates, creating tiny cracks that let water in. Once moisture reaches bare iron, rust forms and pushes the seasoning outward, creating bubbles that eventually flake off.

Addressing rust beneath seasoning requires aggressive intervention. Strip the pan completely to bare iron using electrolysis, oven cleaner method, or thorough scrubbing with a 50/50 vinegar-water solution. Remove all rust down to smooth metal, then dry immediately and apply fresh seasoning. If you catch it very early, you might sand the affected area lightly and re-season locally, but full stripping ensures the problem doesn’t spread.

Prevent Future Seasoning Problems

The best solution to cast iron seasoning problems is preventing them from happening in the first place. A few consistent habits protect your seasoning investment for decades.

Proper heating before adding oil prevents food from sticking and protects seasoning. Always preheat your pan slowly over medium heat for several minutes before adding cooking oil or food. This allows the entire pan to reach temperature evenly, ensuring oil spreads properly and food releases immediately upon contact. Cold pan + hot oil = degraded oil that bonds poorly and sticks.

Avoid cooking highly acidic foods in well-seasoned pans or limit their exposure time. If you make tomato sauce in cast iron, cook it for the shortest time necessary and transfer immediately to a storage container. Acidic ingredients don’t destroy seasoning instantly, but prolonged exposure accelerates breakdown. Many enthusiasts reserve their most prized pans for searing and frying while keeping a dedicated pan for acidic dishes.

Clean promptly and correctly after each use. Hot water and a stiff brush suffice for most cleaning—avoid soap unless necessary, and never soak the pan. Dry immediately with heat (place on low burner for a minute) to evaporate all moisture, then apply a thin layer of oil while the pan is still warm. This maintenance coat replaces any seasoning that wore during cooking and protects against moisture.

Store pans in a dry location with adequate air circulation to prevent moisture accumulation. Stacking pans without protective layers between them traps moisture and causes rust. Use paper towels between stacked pans to absorb any residual humidity and prevent scratching.

Seasoning problems frustrate even experienced cast iron users, but they almost always stem from identifiable causes with straightforward solutions. By understanding the chemistry behind polymerized oil, recognizing early warning signs of failure, and following proper technique for both building and maintaining your seasoning, you can keep your cast iron performing beautifully for generations. The few minutes spent learning these principles pays dividends every time you cook with a perfectly seasoned, naturally nonstick pan. When you encounter cast iron seasoning problems, remember that most issues are fixable with patience and the right approach—your pan’s potential for excellent performance remains intact with proper care.